Should governments delay the second dose of COVID vaccines, administer lower dosages, or otherwise depart from protocol in order to vaccinate more people earlier?

Overview of the dilemma

Nir Eyal, Henry Rutgers Professor of Bioethics, Rutgers Center for Population-Level Bioethics

The three vaccines for COVID-19 authorized for emergency use in some Western countries as of mid-January 2021—by Moderna, Pfizer (and BioNTech), and AstraZeneca—were tested for two doses, 3-4 weeks apart. In recent weeks, however, several options for lower dosing, spaced vaccinations, or mixing and matching different vaccines have been discussed:

I. One and a half dose: By mistake, AstraZeneca tested on some participants a regimen of 1.5 dose instead of 2, and these participants did even better than other groups, constituting very limited evidence in support of an unconventional 1.5 dose regimen.

II. A single dose in a single jab: Some suggested experimenting with giving only one dose of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in order to save more doses for others, on grounds that in trials of both vaccines the sharpest drop in disease in the vaccinated group started before active-arm participants received the second dose. Others suggested that rolling out single doses is justified even without further experimentation, because of the expected public health windfall from vaccinating more people earlier, and because some unconventional evidence already exists that even a single dose probably works, in their view, sufficient evidence to warrant the “gamble”.

III. Spacing out: The UK’s Chief Medical Officers decided to lengthen to 12 weeks the interval between doses of the Pfizer-and AstraZeneca vaccines, which had been authorized for use in the UK with 3-4 weeks between doses. The main goal was to reserve doses for vaccinating more people earlier. In the US, many opponents warned about the dearth of trial evidence in its support. But on an assumption of 52% efficacy after a single dose, modeling suggested that giving the first shot to more people, rather than keeping enough to ensure a second dose at 3-4 weeks, would prevent more cases of COVID-19. And President Biden announced that he would immediately deliver all doses available (that is, if any are), which would mean spacing out doses. The UK is now moving fast on immunizing the population and claims to have evidence of clinical benefit from even further spacing of the AstraZeneca vaccine. Israel, however, is reporting that the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine is less effective in the field than one might have hoped.

IV. A single dose divided into two half-dose jabs: Some American experts are excited about the option of distributing Moderna’s vaccine into two half doses instead of two full ones. There is some data to support it, per senior US proponents, though others oppose this option as well. While a lower dose may or may not enable more vaccine to be distributed early on, it would definitely leave more vaccine for others.

V. A single dose of one vaccine followed by one of another vaccine: While this wouldn’t reduce by much the number of doses needed, it should resolve logistical issues for a second vaccination when the original vaccine is locally unavailable. Yet, the vaccines were tried with two doses of a single vaccine.

Many crucial factual questions remain open. What is the likeliest efficacy of the various dosing and spacing approaches? What are the not-very-unlikely worst case scenarios for each (is undermining public trust, or creating vaccine resistance, likely? Does sheer discussion of these options already confuse the public and undermine trust?), and how bad would they be? There are some conflicting signals even in the evidence we have. For example, in the Moderna trial, there were fewer cases in the active arm than in the control arm after a mere two weeks from first vaccination; indeed, some commentators added, “Because [usually] we do not expect a protective immune response in the initial 14 days after immunization, this suggests that once immune response is more mature, the efficacy of a single dose may be higher”. However, in early testing, the vaccines had seemed quite inefficacious after a single dose—their promise of efficacy was then suggested only after two doses.

There are also questions in philosophy of science and epistemology. How should we understand the likelihood that a regimen that wasn’t tried as such will work, fail to work, or cause harm? Can we put a number on those chances?

Moral questions also surface.

1. Protecting population health vs. protecting individual health: In a pandemic, many accept that health authorities should generally prioritize population needs over those of individuals. But some may doubt that it is ever OK to give a patient less certainty of any effect whatsoever from an intervention in their body, pandemic notwithstanding.

2. Maximizing beneficiaries vs. maximizing fairness and protection of those at high priority: An egalitarian (pro-equality) argument for option II above was that “providing effective protection for as many people as soon as possible is more ethical because it distributes the scarce commodity more justly.” An argument for option III was fairness to priority groups, which would often serve equality as well: “In terms of protecting priority groups, a model where we can vaccinate twice the number of people in the next 2 to 3 months is obviously much more preferable in public health terms than one where we vaccinate half the number but with only slightly greater protection.” But what if a major effect of these diversions from maximal protection of vaccine recipients is to significantly lower the protection conferred to the initial recipients, who are usually in priority groups? Would that suboptimal protection of those with the strongest entitlement and, sometimes, the strongest moral claim to protection be sufficiently condoned by the earlier vaccination of more members of lower-priority groups?

3. Maximizing human health vs. maximizing rich-country population health: In the US, the manufacturers, some serious experts, and the FDA remain skeptical of any departure from authorized protocols, and other serious experts support such departures, which they think is likelier to promote US public health. But options I and IV above, compared to the authorized regimen, would leave far more doses within manufacturers’ production capacity available for other nations. That alone could free up (for purchase or donation) enough doses to vaccinate Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and large swaths of Latin America, even without any COVAX- and other incoming vaccines. Couldn’t this momentous humanitarian benefit break up the tie on what is very best for US public health, and decide in favor of low-dose options?

FDA Emergency Use Authorization requires adherence to

dose and dosing schedule

Eddy

Bresnitz, Medical Advisor to the New

Jersey Department of Health on the COVID-19 response

On January 31, 2020, the Secretary of US Department of Health and Human Services declared a Public Health Emergency under section 319 of the Public Health Service Act in response to emerging COVID-19 infections in the US. This declaration allowed the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to “…allow unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products to be used in an emergency to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening diseases (…) when there are no adequate, approved, and available alternatives” and the benefits of the intervention outweigh the risks.

In December 2020, the FDA issued EUAs on the use of two novel vaccines for the prevention of COVID-19. These EUAs were based on the agency’s thorough reviews of data from the pivotal trials, and on recommendations from its Vaccine and Related Biologics Professional Advisory Committee. The two vaccines were developed on a messenger RNA (mRNA) platform, a technology that had no precedent of a licensed vaccine. Both vaccines were tested as two-dose series, with doses separated by either 3 or 4 weeks. The pivotal trials indicated that, after the second dose, both vaccines had a vaccine efficacy (VE) of approximately 95%, with similar VE in various sub-groups (age, race, ethnicity, underlying medical conditions). The trials also showed that the vaccines caused significant reactions at the site of injection, such as pain or swelling, and systemic reactions such as fever, headache, muscle pain and fatigue; however, these effects were mild to moderate, lasting 1 to 3 days, and were self-limited. Based on these findings, the FDA considered that the benefits of both vaccines outweighed the risk and issued the EUAs.

The EUAs require that healthcare providers use the vaccines as described in the authorizations. The salient requirement is that the vaccines be used in a two-dose regimen, with the second dose given at 3 or 4 weeks after the first, depending on the vaccine. Health care providers are obligated to adhere to the requirements of the EUA. Following issuance of the EUAs, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the CDC issued guidance on interim clinical considerations of the use of mRNA vaccines based on the conditions of the EUA.

A surge in the pandemic beginning in the fall of 2020, and increasing incidence of disease in 2021, motivated a discussion in the scientific literature and the media about changing the dosing regimen in order to more quickly vaccinate a larger share of the public with a single dose. This debate prompted the FDA to issue a statement expressing concern about changing vaccine regimens, given the available data: “Using a single dose regimen and/or administering less than the dose studied in the clinical trials without understanding the nature of the depth and duration of protection that it provides is concerning, as there is some indication that the depth of the immune response is associated with the duration of protection provided. If people do not truly know how protective a vaccine is, there is the potential for harm because they may assume that they are fully protected when they are not, and accordingly, alter their behavior to take unnecessary risks. (…) Until vaccine manufacturers have data and science supporting a change, we continue to strongly recommend that health care providers follow the FDA-authorized dosing schedule for each COVID-19 vaccine.”

At this point, neither the ACIP nor the CDC have issued recommendations or guidance on altering the dosing or schedule for administering these vaccines. Without FDA authorization, ACIP recommendations, and CDC guidance, states and health care providers are unlikely to recommend use of the vaccine outside of the requirements of the EUAs. Until vaccine manufacturers provide additional data that would support altering the dose or schedule to the FDA, the current authorized emergency use of the vaccine is likely to remain unchanged.

Consistent messaging is

key to our public health mission

Phyllis

Tien, Professor of Medicine,

UCSF

Phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine trials in the US are currently

ongoing, and two vaccines have received an Emergency Use

Authorization (EUA) from the FDA. The design of these Phase

3 trials were based upon careful review and analysis of data

from Phase 1 and 2 trials that tested different vaccine

doses for effectiveness as well as safety. We are now also

in the midst of a COVID-19 surge that is worse than nearly

one year ago, and further compounded by increasing reports

of mutated strains of SARS-CoV-2, possibly more infectious

and transmissible, circulating in communities. As a result,

distributing vaccines rapidly is of critical importance to

public health, but dosing and dose scheduling should be

based upon the available scientific data.

Consistent messaging regarding prevention efforts including vaccine dosing, vaccine scheduling, mask-wearing and social distancing are needed to maintain public trust. Mixed messaging in our national response to the pandemic has likely aggravated barriers to the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out, including vaccine hesitancy and fear of adverse effects from the vaccine among parts of the population. Still, many among us are eagerly awaiting vaccination in order to return to some normalcy. Until a significant proportion of our population is vaccinated, it remains critical to send a clear message that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risk, and, even for those vaccinated, precautions such as masking and social distancing must be adhered to.

On the bright side, with the advent of potentially new vaccine candidates that could obtain an EUA by early spring, and the promise of consistent public health mandates to curb the US pandemic, we may be able to accomplish both our public health mission of distributing vaccines in a timely manner while also adhering to the available scientific data.

If changing the vaccination protocol stops the

pandemic sooner, change it!

Dan

Hausman, Research Professor of

Bioethics, Rutgers Center for Population-Level

Bioethics

Two goals govern policy for COVID-19 vaccination: saving lives and preventing other harms from COVID-19; and ending the economic fallout from the public health measures imposed to limit the spread of the virus. These goals are largely, but not perfectly, aligned. In an emergency such as the current pandemic, consequentialist reasoning comes to the fore. Although policies should (of course) avoid violating rights, the central ethical questions are factual questions: which vaccination policies stop the pandemic most rapidly without causing other untoward consequences of comparable importance?

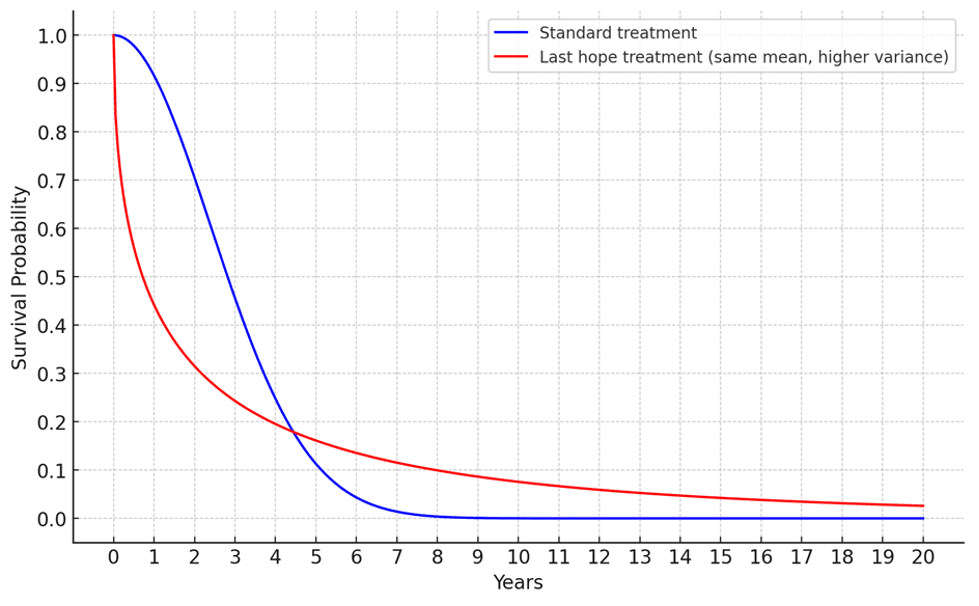

If delaying the second dose or lowering dosages is ineffective at preventing disease, then clearly neither should be adopted. If these measures are just as effective at preventing disease as the current protocol, then the second dose should be delayed or the dosage lowered. This conclusion might be questioned, because the confusion and doubts caused by a change of protocol might wind up deterring people from being vaccinated and thereby prolonging the pandemic. This disastrous consequence is highly uncertain. In circumstances such as these, where the immediate positive effects of an action are certain and the harms are speculative, I think that one should proceed with the action.

The facts seem to be that a single dose or two half-doses of any of the three vaccines whose emergency use has been authorized provide less protection than the standard two doses; and it is unknown how quickly the protection provided by a single dose will fade or what effect a delayed second dose will have. Formal modeling can tell us the consequences of assumptions concerning relevant but unknown parameters, and sensitivity analysis can give us some confidence concerning the risks that changing the protocol will have bad effects. The wild card again is the damage that confusion and doubt may cause. I would make the same response: proceed with the action.

Unless a single dose or two half doses turn out to provide poor and short-lived protection against disease and against transmission, those reluctant to be vaccinated will see their unvaccinated neighbors getting ill, unlike their vaccinated acquaintances. Will the qualms engendered by changes in protocols outweigh this persuasive experience?

If splitting doses and deferring the second dose have immediate effects in limiting disease and infection, then the change in protocol is warranted, even if there is a potential medium- or long-run risk of undermining confidence in vaccination. There is no issue of physicians violating their obligations to patients, because physicians are not making the dosing decisions; and no rights are being violated. So the policy question boils down to the empirical question of which policy stops the pandemic more rapidly. There is no way to know for sure; but, with thousands dying daily, let’s do whatever will help today and worry tomorrow about more speculative harms.

Can spacing out vaccination be justified to all?

Bastian Steuwer, Postdoctoral Associate, Rutgers Center for Population-Level Bioethics

Bottlenecks in distributing COVID-19 vaccines have led to a slower than hoped-for start of the vaccination program in many countries, including the United States. The United Kingdom has taken the unusual step of putting on hold the distribution of the second vaccine shot and using the available doses to vaccinate more people with a first dose.

The UK Chief Medical Officers’ rationale for taking this step was that doing so maximizes the number of people receiving vaccines, and thereby saves the most lives in the aggregate. In part, what underlies this thinking are contested scientific matters. Vaccine efficacy trials tested two-dose regimens. There are only preliminary and less reliable data from these trials showing efficacy from the first dose. The UK Chief Medical Officers estimate a level of protection of over 70 percent. Other writers have been more optimistic, citing 80 to 90 percent protection. Less optimistic data suggests that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is 52 percent effective before the booster shot, although alternative statistical analysis may show it to be higher.

The question is not, however, exclusively scientific. An optimistic answer to the scientific question raises an ethical question: is it ethically defensible to lower the prospects of some by failing to give them a booster shot in order to improve the prospects of others by giving them a first shot?

This is a question of population-level bioethics. We need to consider the health of everyone in society, instead of adopting the perspective of a clinician charged with the interest of their patient. One contrast in population-level bioethics that is helpful for reasoning about this dilemma is the contrast between aggregative and non-aggregative reasoning. Aggregative reasoning asks about the population-level effects, as in the rationale employed by the UK Chief Medical Officers: the overall number of lives saved would be higher, they reason, under a policy of spacing out vaccines. The overall amount of benefits in terms of lives saved justifies the lesser protection afforded to those who will not receive their second shot as planned. Non-aggregative reasoning, by contrast, asks whether a policy can be justified to each individual: instead of justifying a social decision by the aggregate effect, we need to ask whether any individual could object to the decision. One might think that from this perspective the UK’s decision is problematic. Could not a person who will not receive their second shot as planned object that they now have to live with less than optimal protection?

However, I want to suggest that there is a non-aggregative rationale for spacing out vaccine doses. Our current vaccine priority-setting is already following such an approach. It is informed largely by trying to identify individuals at highest risk to give the vaccine to them first. The idea is that those at high risk have a stronger claim to the vaccine than those at low risk.

Consider a simple model of distributing vaccines. We start to give out as many doses as are being produced to persons at high risk. We continue this for three to four weeks, and then we face a choice: do we now give new vaccine doses to the originally vaccinated persons, thereby increasing their level of protection from the preliminary level to the full efficacy level? Or do we give the new doses to not-yet vaccinated persons, thereby giving them some preliminary protection? The originally vaccinated persons should no longer be treated with the same initial priority. Their risk has already been reduced, and their claim to a further risk reduction will not be as strong as the initial claim they had when they were at higher risk. Perhaps we should treat a person aged 75 who has received one shot of the vaccine like a person aged 65 who has not been vaccinated yet.

Whether we should space out vaccine doses, then, depends in part on our overall speed of vaccination. Continuing with my simple model, if after three to four weeks everyone over the age of 65 is already vaccinated and the choice is between persons aged 65 and persons aged 75 who have been given the first vaccine shot, then spacing out achieves little. However, if even after three to four weeks there is still a number of unvaccinated people left who are at higher risk, then spacing out appears more reasonable.

This simple model, as all simple models, leaves out many important considerations. It does not consider indirect effects on either vaccine hesitancy or on vaccine resistance, and it depends on finding a reasonable estimate for the level of protection from the available data. What the model suggests, however, is that opposition to aggregative reasoning does not directly translate into opposing a policy of spacing out vaccine doses.

Now that some COVID vaccines have been authorized, can it be ethical to (continue to) test these and further COVID vaccines, and how?

Overview of the dilemma

Nir Eyal, Henry Rutgers Professor of Bioethics, Rutgers Center for Population-Level Bioethics

Several Western countries have now authorized use of the first few COVID-19 vaccines following placebo-controlled efficacy testing. More vaccines may be authorized in the next few weeks. But further COVID vaccine research, of the following types, remains necessary:

I. Continued/new studies of authorized or approved vaccines in the conventional regimen, e.g. to ascertain their impact on infection and infectiousness, the correlations and duration of vaccine protection, their success against new viral strains, their efficacy and safety in population groups excluded from the initial studies such as children and pregnant women, ratios of rare complications, and impact outside the trial setting. The original trial results and the swabs collected from trial subjects before unblinding get at some of these questions, but there is room for more.

II. New studies of authorized or approved vaccines under new regimens (e.g. on spaced out dosing regimens, or half-doses—see our previous Dilemma).

III. New studies of new vaccines. New vaccines remain necessary should authorized vaccines turn out to have short-lived efficacy, or to protect recipients without reducing their infectiousness to others; and for areas of the world where authorized vaccines are impossible to store, deliver, or procure.

This necessary research could be a combination of (a) epidemiological observations, (b) collecting more samples in existing trials or even switching subjects between trial arms—a “blinded crossover”, (c) temporally controlled field trials (e.g. initiating a new trial that would compare people who receive the authorized vaccine early to ones who receive it later), (d) placebo controlled field trials, (e) active controlled field trials (e.g. comparing authorized vs. promising new vaccines), (f) immune-bridging studies, or (g) challenge trials.

Outcomes of interest could include (i) infection status and level; (ii) disease status and level; (iii) likely infectiousness status and level; (iv) immune response status and level (as in an immune bridging study); (v) adverse events; (vi) some of the former outcomes among participants’ contacts.

Such studies could take place in (1) countries in which the approved vaccines are already being rolled out to some people (either among those people and/or their contacts, or in other people and/or their contacts), or in (2) global populations who will not have access to currently-approved vaccines anytime soon.

This Dilemma explores which combinations of object of study (I-III), research type (a-g), outcome type (i-vi), and study population type (1 and 2) might be ethically permissible.

Many bioethicists would consider it unethical to give placebo to a control group when a known safe and effective vaccine exists. That is worse for their prospects and, normally, for those of their contacts. These bioethicists would especially object when the vaccine being tested has already been approved or authorized. They would be furious if the participants put on placebo would otherwise have access to the tried and tested vaccine outside the trial. But not all bioethicists consider placebo control unethical under these circumstances. And there may be a way around some of the ethical complications here. In particular, for a limited period, some in rich nations where vaccines are rolling out will lack access (e.g. young and healthy people who are not considered frontline or essential workers), such that their immediate prospects will not be worsened by being in a trial. Can very short trials in these populations provide helpful outcomes?

Similarly, the prospects of those who would not have access to the proven vaccine outside of a trial (say, populations in less-developed countries who will not get the vaccines for some time) would not be worsened by placebo-controlled trial participation. These participants’ own nations may stand to benefit greatly from the development of vaccines that are easier for them to procure or deliver. In the past, a WHO group on placebo controlled vaccine studies in developing countries noted a number of conditions that may justify use of placebo for vaccines already known to be safe and efficacious. Still, is it ethical to rely on these populations’ lack of access to the tested vaccines, when that lack of access results from rich/vaccine producing nations’ having hoarded or outbid potential participants’ nations? Does it matter who does the testing, what nations are likely to use the product, and whether post-trial access is guaranteed to participants and their fellow citizens?

And is the ethical challenge limited to placebo control? Any controlled study compares different options, and once one option is authorized, some of its participants will have to be assigned to an unauthorized option—often, unauthorized for the person’s own protection.

We can probably get some useful data out of careful observations, and much useful data from immune-bridging studies and challenge trials, but this discussion will focus especially on the questions above.

Nir Eyal’s work on this issue was supported by an award by the National Science Foundation (NSF 2039320)

The ethics of continuing trials: does the data

justify the risks?

David Wendler, Senior investigator, Department of Bioethics, NIH Clinical Center

Several vaccines for COVID-19 have been found safe and highly efficacious and are now being made available to select groups through emergency use authorizations (EUAs) and other mechanisms. At the same time, there is still significant value to continuing current trials and testing additional vaccine candidates, raising the question of whether and to what extent it is acceptable to give research participants unproven vaccines and placebos after identification of ones that are safe and efficacious.

Some commentators argue that clinical trials are ethically acceptable only as long as there is insufficient evidence that the intervention offered in one arm is superior to what is offered in another arm, or to what is available outside the trial. This view implies that it would be unethical to continue placebo-controlled trials given the findings of efficacy. It also implies it would be unethical to test other unproven vaccine candidates. This view fails to recognize that the obligations researchers have to their participants are distinct from the obligations that clinicians have to their patients.

Codes and guidelines around the world permit researchers to expose participants in clinical trials, including vaccine trials, to some risks to collect socially valuable data that cannot be obtained in a less risky way. These guidelines reveal that researchers are not obligated to provide placebo recipients with a safe and efficacious vaccine once one has been identified. Instead, researchers are obligated to ensure that any plans to conduct placebo-controlled trials remain ethically appropriate given current evidence.

Continuing a trial after the vaccine candidate has been found to be safe and efficacious can provide an opportunity to collect several types of socially valuable data. Of greatest importance, continuing trials can provide a more reliable and more precise point estimate of the vaccine’s efficacy and offer an opportunity to collect additional safety data, including data on any uncommon or delayed side effects. Continuing trials can also help to assess how long the vaccine’s protective effect lasts; offer insight into the vaccine’s impact in various subgroups, such as older individuals or those with comorbidities; and evaluate whether the vaccine candidate protects against infection itself.

Once a vaccine candidate is found to be efficacious, participants in the placebo arm of that trial are known to be at higher risk of symptomatic disease than the participants in the active arm of the trial. How much higher depends on the chances that participants in the placebo arm will become infected, the risks they face if they are, and how much protection the efficacious vaccine offers. The chances that participants in the placebo arm will be infected depends on the local transmission rate, preventive measures they adopt, and the amount of time they remain on placebo. When participants are on placebo for a short time, the chances of infection are correspondingly low. Remaining on placebo for a few weeks, rather than accessing an efficacious vaccine, poses a low chance of substantial harm. Continuing on placebo for even longer periods also poses a low chance of substantial harm to individuals at low risk for severe disease.

Remaining on placebo for an extended period can pose considerable risks to individuals at high risk of severe disease. The extent of these risks depends critically on what options are available to them. In the setting of few effective treatments and potentially strained hospital systems, receiving placebo for an extended period rather than a safe and efficacious vaccine can pose substantial risks. However, if high risk individuals would not have access to a safe and efficacious vaccine outside of research— for example, when there is only enough supply for the trial or when they are not part of a prioritized group that will receive the vaccine during the time of the trial—receiving placebo in a clinical trial poses few additional risks to them.

There is no algorithm for determining how much social value a given clinical trial has and whether its social value justifies the risks participants face. As a result, IRBs tend to focus on ensuring that a trial has the potential to collect important data and that the risks of substantial harm are low. Trials with the potential to collect data helpful for addressing a global pandemic have considerable social value. Inviting competent adults to participate in such trials can be ethical when doing so poses a small increase in their risk of experiencing substantial harm. This suggests that it can be ethically acceptable to continue a placebo-controlled trial for a short period after the vaccine candidate has been found to be safe and efficacious, even when participants might be able to access the vaccine candidate outside the trial, for example, through an EUA.

By contrast, if continuing the trial does not offer the opportunity to collect socially valuable data, or comparable data can be obtained in less risky ways, continuing the trial with a placebo arm for any length of time would be ethically problematic. Inviting participants who are at low risk of severe disease to remain blinded and stay in the trial for a longer period can be acceptable when it offers the potential to collect data that might be helpful for addressing the pandemic. In most cases, continuing a blinded, placebo-controlled design with high-risk individuals for longer periods will not yield data of sufficient value to justify it. Exceptions might include when the individuals cannot access an efficacious vaccine outside the trial and their participation is needed to collect valuable data, or they are in a group for whom no efficacious vaccine candidate has been identified.

Otherwise, individuals at high risk of severe disease should be unblinded and those on the placebo arm offered the vaccine within a redesigned study or given the opportunity to seek the vaccine outside the trial. When the value of the data to be collected does not justify the risks of continuing the trial as designed, researchers have several options. They can unblind participants, offer placebo recipients the vaccine, possibly as part of an expanded access program, and follow them to collect additional data. Alternatively, researchers might redesign the trial, for example, to include a crossover in which the blind is maintained and those on the placebo arm receive the vaccine after they complete the placebo arm. Finally, in some cases, it may make sense to simply stop the trial and unblind participants, thus allowing those in the placebo arm to seek the vaccine elsewhere.

Let’s distribute the “standard of prevention”

equitably before testing new vaccines

Rieke van der Graaf, Associate Professor, University Medical Center Utrecht, Julius Center for Primary Care and Health Sciences, Department of Medical Humanities, Netherlands

To answer the question whether it can be ethical to continue to test further COVID vaccines now that some COVID vaccines have been authorized it may first of all be helpful to look at relevant international ethical guidance documents. For example, the CIOMS guidelines (2016) set out that

As a general rule, the research ethics committee must ensure that research participants in the control group of a trial of a diagnostic, therapeutic, or preventive intervention receive an established effective intervention. Placebo may be used as a comparator when there is no established effective intervention for the condition under study, or when placebo is added on to an established effective intervention.

When there is an established effective intervention, placebo may be used as a comparator without providing the established effective intervention to participants only if:

- there are compelling scientific reasons for using placebo; and

- delaying or withholding the established effective intervention will result in no more than a minor increase above minimal risk to the participant and risks are minimized, including through the use of effective mitigation procedures.

The CIOMS guidelines also explain that “established effective interventions may need further testing, especially when their merits are subject to reasonable disagreement among medical professionals and other knowledgeable persons” and that in some cases this may include testing against placebo. At the time of this writing, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are authorised for Emergency Use by the FDA in the United States and by the European Commission, following evaluation by the EMA, to prevent COVID in respectively the United states and European Union. In the EU also the AstraZeneca vaccine has been authorised. The FDA found no specific safety concerns and determined, for one of them, that “the vaccine was 95% effective in preventing COVID occurring at least 7 days after the second dose”. CIOMS defines an established effective intervention as follows: “an established effective intervention for the condition under study exists when it is part of the medical professional standard. The professional standard includes, but is not limited to, the best proven intervention for treating, diagnosing or preventing the given condition.” Given the absence of safety concerns, the high effectiveness of these vaccines and the fact that they have been authorized in the EU and the US for prevention of COVID, these vaccines seem to fall in the category of an established effective preventive method.

At the same time, there can be legitimate reasons to do further testing despite this standard because there are still many uncertainties, as set out in the overview of this dilemma. Whether this testing can be done in the form of randomization is a further question. In the short-term there may be participants who are not yet eligible for vaccination outside the trial. But in the longer term, there will be a tipping point where vaccination through the regular national health program provides people with an established effective vaccine earlier than with the experimental vaccine. Researchers, sponsors and research ethics committees should be sensitive to that moment while approving new trials. Moreover, at some point, the world will regard the now-authorized vaccines in the EU and the US as part of the so-called standard of prevention package: a term used in discussions of HIV prevention methods, designating the comprehensive package of methods to prevent HIV, including condoms, and pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis, which are approved for clinical use (see UNAIDS, Van der Graaf et al and Singh). In HIV prevention trials all participants (both in the experimental and control arm) must receive access to this package that is recommended by WHO. It is reasonable to assume that for COVID a similar package of preventive methods will come into existence that is recommended by an organization such as WHO. This package then may consist of a range of preventive methods running from hand hygiene and facial protection to vaccines. This package may provide participants with more protection, while making it more complex to start new trials for preventive methods, not only for vaccines, but also for other preventive methods such as monoclonal antibodies when used as a prevention strategy. This dilemma is well-known within the field of HIV prevention.

Another question is whether it is ethical to develop and test new vaccines in low-resource settings that do not have access to the vaccines available in the US and the EU. The CIOMS guidelines recognize that there is a dilemma when placebo-controlled trials are proposed in a low-resource setting when an established effective intervention cannot be made available for economic or logistic reasons:

In some cases, an established effective intervention for the condition under study exists, but for economic or logistic reasons this intervention may not be possible to implement or made available in the country where the study is conducted. In this situation, a trial may seek to develop an intervention that could be made available, given the finances and infrastructure of the country (for example, a shorter or less complex course of treatment for a disease). This can involve testing an intervention that is expected or even known to be inferior to the established effective intervention, but may nonetheless be the only feasible or cost-effective and beneficial option in the circumstances. Considerable controversy exists in this situation regarding which trial design is both ethically acceptable and necessary to address the research question. Some argue that such studies should be conducted with a non-inferiority design that compares the study intervention with an established effective method. Others argue that a superiority design using a placebo can be acceptable. The use of placebo controls in these situations is ethically controversial for several reasons: 1. Researchers and sponsors knowingly withhold an established effective intervention from participants in the control arm. However, when researchers and sponsors are in a position to provide an intervention that would prevent or treat a serious disease, it is difficult to see why they are under no obligation to provide it. They could design the trial as an equivalency trial to determine whether the experimental intervention is as good or almost as good as the established effective intervention. 2. Some argue that it is not necessary to conduct clinical trials in populations in low-resource settings in order to develop affordable interventions that are substandard compared to the available interventions in other countries. Instead, they argue that drug prices for established treatments should be negotiated and increased funding from international agencies should be sought. When controversial, placebo-controlled trials are planned, research ethics committees in the host country must: 1. seek expert opinion, if not available within the committee, as to whether use of placebo may lead to results that are responsive to the needs or priorities of the host country…; and 2. ascertain whether arrangements have been made for the transition to care after research for study participants …, including post-trial arrangements for implementing any positive trial results, taking into consideration the regulatory and health care policy framework in the country.

The particular dilemma for COVID may be that vaccines are

for logistical reasons proposed to be tested against placebo

and are already known to be less safe and effective than the

vaccines available in the EU and the US. On the one hand, as

long it is reasonable to assume that these trials may lead

to a vaccine that is easier to scale up than existing ones

and so help to stop the pandemic in these settings, this may

be an argument in favour of starting these trials. On the

other hand, what currently seems to make the start of new

vaccine trials for local production in low-resource settings

impermissible is that

172

countries have made agreements by means of

Covax

to secure “2 billion doses from five producers, with options

on more than 1 billion more doses” (see

WHO).

These doses have not been delivered yet, but the aim is to

make them available before the end of 2021. Before

considering and approving further trials in resource poor

settings, research ethics committees, researchers, sponsors,

manufacturers, national health authorities, regulators and

others should consider whether more can be done first to

ensure global equitable access to existing COVID vaccines

through Covax.

A more favorable view of (some) trials in developing

countries

Brian Berkey, Assistant Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Despite the fact that we now have several authorized COVID vaccines, continued research remains necessary. Some of the trials that could provide valuable information require that at least some participants don’t receive one of the authorized vaccines during the trial period. Consider, for example, trials involving new vaccines. These trials are important because new vaccines could have important advantages in comparison with those already approved. They might, for example, provide greater protection against emerging variants of the virus, or be storable at temperatures that would make them easier to distribute in developing countries.

Other trials that could provide valuable information require that participants receive altered regimens of authorized vaccines (e.g. two half-doses instead of two full doses). If these trials were to show that an altered regimen involving less vaccine per person is roughly as effective as the approved regimens, this could allow for quicker vaccination of the global population.

Wealthy countries have procured most of the current supply of the authorized vaccines, and can be expected to control most of it for some time. In addition, these countries are already in the process of vaccinating their populations using the approved regimens. Because of these facts, the prospects for trials of new vaccines and altered regimens of approved ones to be effectively carried out may be greatest in developing countries, where citizens will likely not have access to the authorized vaccines and regimens for some time.

Since there are powerful reasons to think that it’s unjust that citizens of wealthy countries have access to the authorized vaccines long before those in poorer countries will, there are grounds to worry that if trials are conducted in poorer countries while those in richer countries are being vaccinated using the approved regimens, those conducting the trials would be wrongfully exploiting the participants. Some would claim that this is the case even if the participants give informed consent, face limited risks, and may benefit significantly from their participation. One argument for this conclusion relies on the claim that it’s objectionable to take advantage of those who are vulnerable, at least if their vulnerability is the result of injustice. Proponents of this argument hold that taking advantage of unjust vulnerabilities constitutes wrongful exploitation.

I think that the charge of wrongful exploitation would be correct in some cases. Perhaps the most obvious are cases in which trials in developing countries are run by, and stand to benefit, agents that are among those responsible for or benefitting from the injustice in access to authorized or approved vaccines and regimens that makes those countries especially suitable sites for further trials. Consider, for example, the governments of wealthy countries, which, in my view, have acted unjustly by procuring the bulk of current and near-future vaccine supplies for their own citizens, rather than allowing for a more equitable distribution. If these governments were to fund studies in poorer countries with the aim of using the knowledge gained primarily to further benefit their own citizens, this would constitute wrongful exploitation. But importantly, in my view this is primarily because the governments of wealthy countries have an independent obligation to contribute to ensuring an equitable distribution of approved vaccines globally. Instead of funding these trials, they should be funding greater provision of approved vaccines to more of the poor around the world, and seeking to promote further trials that distribute both the risks and potential benefits more justly among the global population. If wealthy country governments did not have these obligations, and the trials could reasonably be expected to benefit the participants and others in the countries in which they might take place, it is harder to see on what basis we might object to them.

Because of this, I think that we should have a more favorable view toward at least some trials that could be run in developing countries, despite the fact that it may only be because of unjust disparities between richer and poorer countries in access to the approved vaccines and regimens that they’re possible. Consider, for example, a pharmaceutical company that hasn’t yet produced an authorized or approved vaccine, but has a promising candidate that requires further testing. If developing countries had access to authorized or approved vaccines that was comparable to what wealthy countries enjoy, running trials in developing countries may not have the prospect of generating results that would be as informative. In a sense, then, if the company runs trials in developing countries, it would be taking advantage of the fact that participants unjustly lack equitable access to approved vaccines.

But since it’s at least plausible that companies that don’t yet have an authorized or approved vaccine aren’t obligated to contribute directly to the equitable distribution of other companies’ authorized or approved vaccines, there’s reason to think that their running trials for promising candidates wouldn’t be wrong. So long as familiar obligations such as securing informed consent and ensuring the safety of participants as much as possible are met, the fact that participants would improve their prospects by taking part, in comparison with the status quo, provides sufficient grounds for preferring that these trials take place.

A more difficult case to assess

is one in which a company that’s produced an authorized or

approved vaccine intends to test alternative regimens in

developing countries that currently lack equitable access to

supplies of that vaccine. If the company is obligated to

contribute substantially to providing equitable access (by,

for example, reserving some of the existing supply and

selling it to poorer countries at a discount), but is

failing to meet that obligation, then running such trials is

wrongfully exploitative. Even if that is the correct

conclusion, however, we likely still have reason to prefer,

from a moral perspective, that the trials are run rather

than not. After all, as long as participants would improve

their prospects by taking part, failing to run them would

leave their unjust disadvantages entirely unaddressed,

rather than mitigated at least a bit. This means that if

there’s nothing that can be done to get the relevant

companies to satisfy their obligation to promote equitable

access to approved vaccines, we shouldn’t attempt to stand

in the way of their running trials that would benefit

unjustly disadvantaged participants.

Unsatisfactory justifications for COVID trials in developing countries

Monica

Magalhaes, Program Manager, Center for

Population-Level Bioethics, Rutgers

University

In developed countries that were able to buy up the first

authorized COVID vaccines early, a complication is arising

for continuing COVID vaccine research. As highly efficacious

vaccines are rolled out to the general population, some

vaccine trial participants and potential participants now

have their health prospects lowered by participating in

controlled studies. Participants are

dropping

out of studies to get vaccinated as they become

eligible, at the expense of the final quality of the data

and of knowledge that would be gained from these studies.

One apparent solution for this complication is to conduct any further COVID vaccine trials in developing countries where vaccination prospects for the vast majority of the population will remain low for the foreseeable future. Where no-one has access to the vaccine outside a trial, no-one’s prospects of accessing a vaccine are worsened by participating in a trial. The concern about this option, as put in the overview of this dilemma, is that this justification relies on much of the world’s population lacking access to the same vaccines that are, or will soon be, widely available for the minority living in richer nations. That seems to be unjust, or at least exploitative of an injustice.

As with any disease, someone(s) will have to be in the studies that will continue to advance COVID prevention and treatment after the first line of prevention and therapy is found and made available. Studies that withhold or withdraw proven interventions to test experimental interventions raise particular ethical concerns, but they are not unique to COVID—as Rieke van der Graaf explains in this dilemma, this ethical territory has been trod before and we have guidelines and years of debate in research ethics to show for it. And yet, the fact that someone has to do it does not seem like a satisfactory justification for the fact that these someones will predictably be in developing countries where access to vaccine will be unjustly slower to arrive.

One possible way to justify this predictable outcome is to argue that, even though background inequalities are unjust, trials in developing countries are justified by the individual benefits to participants whose health prospects are increased by participating in the trial; and by the societal benefits of improved prospects for the participants’ compatriots’ access to vaccines, compared to what their prospects would be had the country not hosted trials. This seems unsatisfactory too, because these societal benefits will go only as far as the trial sponsors’ post-trial obligations or agreements extend (a simple obligation to provide the vaccine to all trial participants would not do much for the country), and only as far as these obligations or agreements are enforced or lived up to. Developing countries are rarely well-placed to demand or enforce strict obligations from large corporations based in developed countries, or from developed countries themselves; and hosting a trial has yet to catapult a poor country towards the front of the line.

Another way to soothe worries about relying on background inequities in access to vaccines is to appeal to the expectation that trial findings would benefit mainly poorer countries and their populations—for example, in trials seeking to establish safety and effectiveness of new vaccines that are cheaper or easier to store, transport, or administer. But this too is only persuasive up to a point: the benefit from discovering alternative vaccines will accrue to the entire world, as lower costs and easier logistics would help even the richest of countries to get their populations vaccinated sooner and faster. While it is true that developing countries need these benefits more, that rationale itself relies on developing countries’ lower level of resources for health, health personnel, and infrastructure. This line of thought should refocus, rather than appease, our equity concerns.

As vaccines start to roll out,

we all watch as the gap between rich and poor countries

predictably widens. A

“catastrophic

moral failure” results from

institutions

that enable vaccine nationalism by countries that

can pay the highest prices, to the exclusion of much of the

world. We ought to remain uneasy about relying on those

without access to vaccines to participate in future

COVID-related research. Globally fair distribution of the

risks, burdens and benefits of the COVID research that

remains to be done requires globally fair distribution of

effective vaccines and interventions.

Vaccine trials in the developing world, exploitation, and post-trial responsibilities

Daniel Wang, Associate Professor, Fundação Getúlio Vargas School of Law, Brazil

By joining a placebo controlled COVID vaccine trial in a vaccine-deprived developing nation, individual participants will not lose anything that they would have received had they not joined the trial. Nobody is made worse-off by participating in such research. Indeed, some or all will gain. Those who participate will have at least the possibility of being vaccinated effectively against the disease. In addition, every participant (including those in the placebo arm) will usually benefit from additional tests (which are usually more beneficial than burdensome) and (if the trial is otherwise conducted ethically) from optimal care during and after the trial if they fall sick. In short, placebo controlled trials are Pareto improvements (because they harm no one and benefit some), and perhaps strong Pareto improvements for the primary stakeholders (because they may benefit participants, certainly ex ante and by and large ex post).

Moreover, even for those in the placebo arm, the risk of having serious COVID may not be enormous if compared with the risks normally accepted in clinical trials. Certainly if the use of placebo is accepted in countries where vaccines have been approved, then it must be accepted in vaccine-deprived countries.

From the perspective of communities, the countries where access is currently limited or inexistent are the main beneficiaries of more trials. They are far behind in the race for accessing approved vaccines and will benefit from more options. Research for vaccines that are cheaper and easier to administer are particularly responsive to the health needs of these populations. Even if this is not the case, more competition means more vaccines available in the global market, which would possibly facilitate access, reduce price, and give countries some bargaining power in negotiations with pharmaceutical companies.

Any “exploitation” objection to placebo controlled COVID vaccine trials in countries without vaccine access is far more plausible in situations where sponsors do research in vaccine-deprived countries but sell their products, once approved, exclusively (or mostly) in the developed world. It is then important that sponsors are committed to fulfilling their post-trial responsibilities. At a bare minimum, they need to guarantee vaccine availability in the country where the trial was conducted. Sponsors must be committed to applying as soon as possible for regulatory approval (including emergency/conditional approval) of their products in the countries where they conducted their trials (see CIOMS, Guideline 2) and to distributing their successful vaccine products there.

Availability, however, does not guarantee access. Availability refers to the presence of an intervention in an intended place and time, while access refers to the use of such treatment by an individual. Sponsors need to make reasonable efforts to promote access, for instance, through donation, price reduction, technology transfer, training, and support to build infrastructure. The more is done to promote access, the lesser the concern about exploitation.

Conducting research in low-resource settings often raises difficult ethical questions. What constitutes exploitation? Should mutually beneficial exploitation be allowed? Can an intervention be tested against the local standard of care if this is inferior to the best current treatment available where sponsors and researchers come from? What is owed to research participants and their communities? There will be reasonable disagreement about these issues in general and in particular cases, so it is important to consider who will make the decision on whether a trial is ethical.

In many developing countries, there are institutions that apply international scientific and ethical standards to assess research protocols. For instance, in Brazil, where access to approved vaccines is still very limited, vaccine trials cannot take place without the approval of the drugs agency (ANVISA) and the National Ethics Committee (CONEP). The ethics committees/review boards of funding bodies, academic institutions, and companies in the developed world should avoid blocking trials that are Pareto improvements before local institutions are given the opportunity to make their own evaluation on these difficult ethical issues. Such institutions, particularly if they allow public involvement and participation, will probably have a much better understanding of the circumstances and social values in their own countries.

Finally, there is merit in the argument that the insufficiency of approved vaccines globally does not justify allowing in the developing world research that would be unacceptable in developed countries. The root of the problem, the argument goes, lies in global inequality, lack of international aid, and patent laws. However, those making micro-decisions about whether to give an ethical approval for a trial to go ahead will rarely have the power to address these large gaps in global justice.

Testing vaccines when an effective vaccine exists: if that’s all I can get…

Sarah Conly, Professor of Philosophy, Bowdoin College and vaccine trial participant

I was a participant in the Phase III Moderna COVID vaccine trial. I received my two injections four weeks apart in August and September, 2020, and on January 2, 2021 I was very pleased to learn that I had received the actual vaccine, not the placebo.

I was motivated to participate in the trial by three things: First and foremost, I hoped I would get the vaccine, and not the placebo. At that point, and even now (January, 2021) there would have been no other way for me to get access to the vaccine, and, since I am 68, I thought COVID could prove quite dangerous for me. Second, I wanted to contribute to research on the vaccine. Third, I thought it would make a good story, especially for my Bioethics students. I should note that we were also paid by Moderna for each visit to the clinic, but for me that was not a consideration: it was nice, but didn’t affect my decision. The hope of getting an effective vaccine was what led me to brave the two-hour drive from Maine through the hell of Boston traffic, and, of course, to accept the possibility of known or unknown side effects.

This makes me think that offering placebo-controlled trials in places where the vaccine is not available, or to those to whom it is not available even where it exists, is morally acceptable. Of course, there shouldn’t be inequality in healthcare around the world, but there is. Given this, I think participants could very rationally decide that the 50% chance of getting a possibly effective vaccine is much, much better than nothing, especially where rates of infection are currently high. Why not take a gamble with positive expected value? Of course, it would be better if there were a vaccine available to everyone everywhere; but since we can’t make that happen, for many people a placebo-controlled trial is the best chance for getting a vaccine. And, of course, it furthers the research that we still need. To me, this makes it a win-win proposition.

Once COVID-19 vaccines are widely available, under what conditions would it be permissible for governments to create “immunity passports” that facilitate conditioning of services on prior vaccination?

Overview of the dilemma

Nir Eyal and Monica Magalhaes, Rutgers Center for Population-Level Bioethics

Societies’ best ticket back to normalcy is, at this time, vaccinating enough of the population to reach or approach herd immunity, particularly if vaccines continue to be shown to reduce COVID-19 transmission. To increase vaccination rates, governments must procure and provide vaccines, remove access barriers, and make the case that the vaccines are safe and efficacious. In addition, governments and institutions can create incentives for becoming vaccinated or disincentives for staying unvaccinated.

One way for governments to achieve that is to institute some form of documentation (a paper card, a smart card, a phone app) to prove vaccination status, which government agencies or private businesses can then require before e.g. rendering services that involve sharing of public spaces. Such immunity passports, or “green passports,” could be required, for example, for boarding a plane, train, bus or taxi, attending a gym or dining in a restaurant, or continuing to work at a hospital, at least absent an up-to-date negative COVID test, evidence of natural antibodies from recent COVID, medical exemption from vaccination, and perhaps other narrowly defined exemptions.

The federal government is creating standards for such passports, and the government of the State of New York is backing a specific initiative. Rutgers University, CPLB’s own home institution, has announced that students will need proof of vaccination (or a medical or religious exemption) to return to campus in the fall of 2021. Such approaches may become trends across US states and US institutions of higher education.

This Dilemma is asking what affects the permissibility of green passports. For example,

-

Does it matter whether only private sector services are conditioned on a green passport, or also government ones?

-

Letting private businesses be the ones conditioning service on passports (which may be in the interests of many businesses, and may save the government from some confrontations) raises a further question: Does it matter whether the government forces, encourages, or merely makes it legal for businesses to condition service on green passports? Leaving individual businesses or institutions free to make their own policy allows for different approaches to be tried (without randomization) and “compete” in the marketplace, but may reduce both the passports’ (perceived) coerciveness and their impact on vaccination rates.

-

Does it matter whether the government’s use of green passports aims to increase vaccination rates, or, alternatively, any such predictable increase is a mere side effect of their use to achieve other aims, such as protecting other users of shared public spaces, increasing public trust in the safety of public spaces, facilitating the reopening of many kinds of businesses and activities, and making those who voluntarily choose not to be vaccinated to internalize the effects of their decisions on others instead of free-riding? What if the government welcomes these side effects of green passports and feels that they would provide ample justification, but is driven by the importance of increasing vaccination rates?

-

Would merely partial (or partially equitable) access to vaccines completely rule out use of green passports, since it would penalize those with deficient vaccine access? Or should these compounded disadvantages merely be added into the overall calculation of the benefits, costs, (in)inequality, and other effects of green passports on equity, many of which will be positive? Could the correct approach lie in the middle, say, adding these compounded disadvantages to the calculus, but lending them extra weight, because they (allegedly) come from the government’s own actions?

-

Does it matter whether the goods and services conditioned on having such passports are “essential” (bus access, in-person school access), or only ��elective” (cruise-ship access, dine-in restaurant access)? If conditioning essential services on vaccination (with appropriate exemptions) makes incentives for vaccination more efficacious, and if those deprived of these services could resume their access at any time by getting vaccinated, then what, if anything, is wrong with conditioning essential services on vaccination? Conversely, could conditioning of even elective services accumulate to a point where the resulting differences in access threaten what political philosophers call “relational equality” by formulating a two-class society? And even if to some degree they do, is this merely an “expressive cost” that is worth paying to save more lives?

-

What will be the effects of green passports on global inequality? If international travel comes to be conditioned on vaccination, many citizens of rich countries and only a select few from elsewhere will probably be able to travel freely, at least for some time to come. Does that ethically rule out the use of these passports? Or should these bad effects be weighed against the potential economic benefits to (many) developing countries of reopening the tourism industry and invigorating rich country purchase of goods and raw materials from developing countries?

-

Are there implementation issues that might threaten the entire scheme?

Immunity passports: what is the true dilemma?

Ruth W. Grant, Professor Emerita of Political Science, Duke University

The key condition that legitimizes limiting access to various services and public spaces to the vaccinated is that the unvaccinated have freely chosen their status. Practically speaking, for this condition to be met, the vaccine has to be readily available to all who want it. If this condition is met, or if COVID tests are readily available and negative results are accepted in lieu of proof of vaccination, it is hard to see an ethical dilemma here. It is an easy call. Governments have a responsibility to act to promote public health and safety. Private enterprises have a similar responsibility, but on different grounds. And individuals do not have absolute freedoms. Individual freedom is always limited by considerations of harm to others. In principle, then, governments may condition services on prior vaccination. And businesses may do the same. Moreover, governments could not prohibit businesses from doing so.

Stated in this way, it looks as if there is no ethical conflict. But to many people, immunity passports would undoubtedly appear to be an illegitimate government imposition on individuals who choose not to be vaccinated. What is the alternative? If the unvaccinated are not excluded, the vaccinated are disadvantaged. They cannot trust that an airplane or a sports stadium, for example, is a safe place to be. The result may well be further delay in the opening of public spaces. In other words, there is not a neutral policy option: either the unvaccinated or the vaccinated will have their options constrained. If this is the case, the choice is clear—it is the unvaccinated who are a threat to others and to the public good. And, as has been true since the start of the pandemic, the same policies that promote public health hasten the opening of the economy.

The really difficult dilemma here, I think, is not on the level of conflicting ethical principles. It is on the level of empirical and political realities. Establishing a vaccine passport system might be perfectly legitimate, and still be the wrong thing to do. In the United States right now, everything related to the pandemic is so politicized, it would be hard to predict whether immunity passports would encourage people to get vaccinated or cause a serious backlash. The details would matter a lot: would a state- and local- level policy be more effective than a national one? How would the limitations on the unvaccinated be enforced, especially where it is private business imposing the constraints? What sorts of public messaging could lead people to see the immunity passport as a welcome step forward in the fight against the pandemic?

How to permissibly distinguish the vaccinated and the unvaccinated

David Enoch and Netta Barak-Corren, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

In a recent position paper, we (and colleagues) outlined the main justifications for policies that distinguish between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated (“green passport policies”), for instance in access to cultural events, leisure activities, indoor dining, and so on. We also discuss the main conditions in which such policies may be morally permissible.

Importantly, our paper is based on the factual situation in Israel in the past months, and it should be read in that context. Perhaps the most important feature of the Israeli context is that vaccines are widely available, free of charge and typically in easily accessible locations, to all within Israel proper. This is how vaccines should be available everywhere else as well. Of course, if vaccines are expensive, unavailable, or not realistically accessible, this strongly affects the permissibility of green passport policies. We here assume a situation in which vaccines are widely and easily available. We also assume that, absent inoculation, high infection rates lead to (justifiable) severe restrictions with harsh economic, social, educational, and other consequences. This is the situation in Israel, in most of the United States, and in many parts of the world.

In such circumstances, for most people, getting a vaccine that has been shown to be both safe and effective is both rationally and morally called for. It is the main way in which one can play a role in the collective effort to battle the essentially collective phenomenon of the pandemic. Yes, some uncertainty about the long-term effects of the vaccines (and indeed of contracting COVID) remains, but given the certain harms, both direct and indirect, of the pandemic, vaccination is clearly called for. This does not mean, of course, that anyone refusing to get the vaccine is to blame, but it does mean that some green passport policies may be justified.

On what terms, though? We argue that green-passport-based distinctions may be justified, as long as they are effective at promoting compelling goals, and as long as they satisfy a proportionality requirement. The justifiable ends we point to include reducing the numbers of infections and controlling pandemic-related harms and derivative general health harms (e.g., lower quality of care due to hospitals congestion); returning to economic and social normalcy; imposing the costs of the decision not to be vaccinated on those making it; and incentivizing inoculation.

The decision about each proposed use of green passports should be made with these ends and with the proportionality requirement in mind, and no general recipe for a decision can be supplied. Here, though, are some important guidelines:

• How pandemics work, and how this challenges traditional categories: A pandemic is, by its very nature, a collective phenomenon. Given this collective nature—and perhaps especially, the exponential pattern of infection—pandemics challenge the traditional liberal protection of a private sphere of a person’s behavior, which is no one’s business but their own. During a pandemic, one person’s decision to not get vaccinated and nevertheless interact with others (often without their knowledge on that choice) imposes costs—often serious costs—on others. This does not mean that people should be forced to get the vaccine, nor does it warrant a vaccination mandate backed by a criminal sanction. It does mean, however, that at least in the paradigmatic case, there is no plausible objection to policies that impose the costs of the decision not to get the vaccine on those making it.

Thus, if the risk of opening up restaurants for indoor dining or campuses for in-person classes is too high in the absence of sufficiently high vaccination rates, there is no reason to make the vaccinated bear the cost of the unjustified decision by others not to get the vaccine. In such cases, then, it is justifiable to open up such activities under green passport restrictions.

• Equality and discrimination: What this means, of course, is that policies that distinguish between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated are not discriminatory. There are relevant distinctions between the groups that justify (some) restrictions on the unvaccinated. Currently there is no similar justification for restrictions on the vaccinated.

• Sensitivity to facts: Such green-passport-based distinctions and restrictions are not a penalty, but rather a form of risk regulation and cost allocation that should be fully sensitive to the ever-changing facts. If, for instance, the rates of vaccination are high enough to approximate herd immunity, so that an individual’s decision not to get the vaccines imposes no cost on others, there will no longer be any justification for restrictions.

• Distinctions, distinctions: Because proportionality is crucial here, different cases must be treated differently. For instance: access to vital locations and services such as polling places and hospitals should remain available to all. Access to places like restaurants and movie theaters, while undoubtedly important, may be restricted. Decisions on specific cases should also be sensitive to the available—even if not quite as good—non-risky alternatives. So long as deliveries are an option, for instance, access to grocery stores may be restricted. Similarly for university campuses, at least as long as distance learning is a viable (if less than perfect) option.

• Trust and incentives: Incentivizing vaccination is a legitimate government purpose at this time. Still, it should be pursued wisely. And some incentivizing measures may be counterproductive. Perhaps in some cases a more effective policy will be focused on attempts to foster trust (especially with populations wherein mistrust of government agencies is both entrenched and arguably justified). Countries where it will take some time until vaccines are sufficiently widely available to make green passport policies a viable option, such as the US, should work on building trust in vaccination now. But the importance of building trust and of rationally convincing people to get the vaccine does not rule out the potential contribution of incentivizing vaccination, or the permissibility of green-passport-based distinctions.

• Equality and impact: Vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy are unfortunately correlated with membership in marginalized groups and with low socioeconomic status. Arguably, then, green passport policies will disproportionately harm the most vulnerable. This is a valid concern, of course, which should affect permissible policies. It should also affect the effort and resources put into establishing trust and rationally persuading the population with regard to vaccines. Notably, however, the indirect effects of the pandemic—of lockdowns and closures, of economic slowdowns, of higher unemployment rates, and so on—also fall disproportionately on the vulnerable and marginalized. So considerations of impact on the most vulnerable cut both ways in this dilemma. Green passport policies, by incentivizing inoculation, protecting from health-related harms, and reducing the economic effects of the pandemic, may ultimately serve an important role in mitigating these negative effects.

For now, benefits are too uncertain to justify green passports

Nicole Hassoun, Professor of Philosophy, Binghamton University

To decide if immunity passports are a good idea, it is important to get clear on: 1) what objectives we are trying to achieve by implementing them; 2) whether passports will achieve those objectives; 3) any ethical problems that remain if they do; 4) whether there are better ways of securing the same benefits without the ethical costs; and 5) whether there are ways of limiting the costs these passports create or expanding access to the benefits they provide.

Some argue that immunity passports will limit health risks while letting economies return to normal—but what risk levels are acceptable? Will passports reduce the risk below that threshold? Can we lower risk levels sufficiently without implementing without passports? And can we compensate people for, or limit, passports' ethical costs?